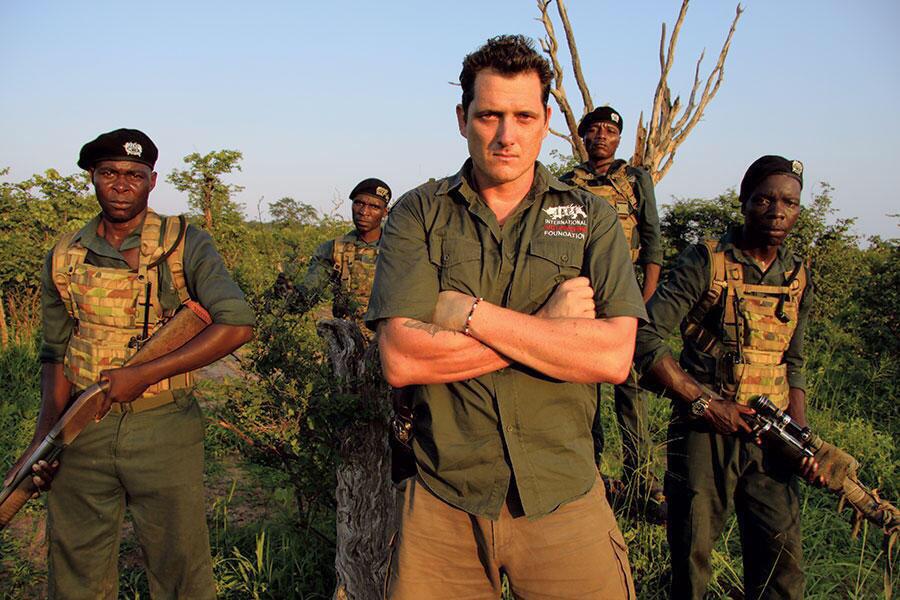

Interview with Damien Mander: The Cause

Following my previous post where we got to know a bit more about Damien Mander, the man who turned a calling into a selfless organisation, we continue by getting insight into the threat that rhino poaching has on the extinction of this species.

I would again like to thank Damien for conducting this interview.

*******

|

| "We are fighting a war, and we need to realise it." - Damien Mander |

The day after we met at the Jane Goodall Institute, I drove through the Kruger National Park trying to spot the Big 5.

Unfortunately I only managed 4 seeing as leopards can be very illusive and

private. But the highlight was seeing a rhino even though only in the distance.

How does it feel to get up close and personal with these majestic beasts?

It’s a very special thing, but at

the same time it is very hard to sit back and relax and say everything’s fine.

You know, animals don’t want much. They don’t ask for a pay check, a fancy house

or fast car. They just want one thing, and that is to live. And we as humans, as

one of five million species on the planet, tend to take that away from them a

lot, and to have the opportunity to be able to protect these animals is

something very special for me and I consider it a great honour. But it doesn’t

stop at wildlife for me. The easiest way to protect animals is simply to not

put them in your mouth. I am a vegan and have chosen to acknowledge that there

is no difference between a rhino and a cow. The only difference is the one we

have allowed ourselves to create in our own minds, so whenever I see an animal

I see something that is innocent, like a child that hasn’t and can’t do

anything wrong and therefore doesn’t deserve to be punished. We, as we term

ourselves as a dominant species, can conquer and divide, rule and crush, or we

can protect. We have those options and it’s up to each and every one of us to

choose what we are going to do to those animals. My choice is to protect.

Other than the obvious setback of man

power in the fight against poaching, a very big issue will be

funding. How do you manage to fund your foundation, IAPF?

A lot of our funding comes from

people around the world who contribute between $10 and $50 a month in an

ongoing way. We are fighting a war here, and I don’t think anybody will dispute

that, and even though wars have a pointy end there is a lot that goes on

underneath that holds that pointy end up. The foundation we have are

supporters all around the world who contribute, some small and some big, and

this means a lot to us when you pool it all together. Initially, setting up as

an Australian organisation, the majority of our funding was coming from there.

That weight has now shifted to the US and Europe, in particular Switzerland, so

we have seen an increase in funding. But to date, less than one percent of

funding has come from the African continent. When setting up the foundation, I

took that mandate, especially in Zimbabwe, to have the luxury of being able to

go overseas and sell our plea. A lot of these people look at these animals with

the view of “It’s Africa’s animals, so why should we help?” but these animals

are a global asset and it’s a global responsibility to protect them.

When writing My African Dream and

deciding to pledge 50% of all book sales to help fund anti-poaching

organisations, I was shocked to find out how many of these used it as a marketing

plan as opposed to a cause, especially when a small percentage of money collected went towards the

actual saving of rhinos and the rest to corporate structures and salaries. How

is IAPF and Damien Mander different?

We are a very lean organisation,

and when I say lean I mean that we don’t have air-conditioned offices in capital

cities all around the world. We are a direct-action organisation and our money

goes onto the front line. We are there to support rangers and make sure they

have the capacity to do their job and do it well. I go to work every day

knowing that IAPF isn’t the ultimate solution, but we try to get the communities

on our side by giving them a reason to not poach, and this is what we are

aiming for but is unfortunately above our pay grade. My time and job is to hold

the fort, so that’s where the funding goes. Being a lean organisation means that

the guy who wrote the mission statement and objectives is still the guy that puts

on a uniform and goes out with the rangers. I’m not stuck in board rooms 365

days a year and everything goes to the ground, whether money or kind donations

of equipment. All this and services offered by people around the world is

fantastic, and we are only able to do what we do because of this kind of support.

The majority of IAPF’s overheads and

operational costs are covered by an in-house commercial operation which is a

volunteer program called Green Army, situated near Victoria Falls where people

from around the world come and spend time with us patrolling next to the

rangers. The money that they contribute to the organisation covers a large sum

of the funds needed for the day to day running of what is soon going to be six

different entities.

In your exposure to the poaching

industry, you have obviously come across rhinos that are either already dead or

are gargling their last breath… Could you, in your own words and for the

benefit of the population out there, tell us what you feel?

Going back to an earlier answer

with regards to animals and how we exploit them, I use the metaphor that a

rhino is the same as Mother Nature, and if we hurt the one we hurt the other.

What we are doing to this species that has evolved over millions of years we

are doing to the planet, and then I got to thinking… The planet has been here

for over five billion years, spinning in space, and has survived a lot worse

than humans. Species come and species go, but it has come down to the rhino and

us, and the hardest thing to protect in the wild is any species. If we can’t

protect that and the eco system is broken down, us as humans won’t have a back

yard to play in. We are paining ourselves further and further into a tight

corner by destroying resources, so when I see a dead rhino I see us as a

species…struggling.

Going back to an earlier answer

with regards to animals and how we exploit them, I use the metaphor that a

rhino is the same as Mother Nature, and if we hurt the one we hurt the other.

What we are doing to this species that has evolved over millions of years we

are doing to the planet, and then I got to thinking… The planet has been here

for over five billion years, spinning in space, and has survived a lot worse

than humans. Species come and species go, but it has come down to the rhino and

us, and the hardest thing to protect in the wild is any species. If we can’t

protect that and the eco system is broken down, us as humans won’t have a back

yard to play in. We are paining ourselves further and further into a tight

corner by destroying resources, so when I see a dead rhino I see us as a

species…struggling.

A proposal has been made to legalise

the trade in rhino horn. Do you think this will in any way help curb the

problem?

We are not an organisation that

focuses on legalising trade or even proposing it, we are an organisation that

focuses on trying to stop rhinos being killed on the front line. Now the

argument you’ll have against trade is as good as the argument you’ll have for it,

and both sides are equally as passionate as the other by putting forward their

argument on either side of the stage. The pro-trade point is that at the moment

a rhino is worth twice as much dead as it is alive and the only proposal on the

table to shift that around is some sort of legalised trade in rhino horn. I’m

also going to say that trade ban has been in place for thirty-eight years, yet

the situation is getting worse and worse. We keep flogging a dead horse and

need to start looking at logical solutions at ground level which will stop a

rhino from being a liability rather than an asset. The anti-trade lobby will

say that, and looking back at 2008 when stockpiles of ivory were opened up to

the market, it will in itself create a higher demand. The pro-trade then say

that rhino horn is different because it grows back as opposed to ivory where

the animal has to die. The anties further say that if this happens, we are

forcing the rhinos into a cattle-like situation where they are bred and preserved

for their horn, and in this way taken from their natural environment.

What I say doesn’t matter either

side, and this because South Africa is sitting on 30 tons of stock-piled rhino

horn. Now at the moment there is a crisis, and whilst there’s a crisis the

option of selling off that 30 tons is being heard in societies. If you do the

maths, on 30 tons not even at the street value of $75,000 a kilogram but even

half that, you’re looking at billions and billions of dollars. If South Africa gets

on top of this problem now, the option of trade being discussed will be taken

off the table because the crisis may seem to be under control. While there’s a

crisis and no trade, the option of selling this at a hefty price remains, and

there’s a lot of people and institutions that will benefit from that. So you

tell me if you think trade will be passed or not?

Then, and if I step on any toes I

actually don’t give a shit, I now know why certain countries stand back while

their rhino population is slaughtered into extinction.

You spend a lot of time in the Kruger

and Mozambique, the park showing the highest percentage of kills in the world…

what would you suggest South Africa do as a country to help prevent this seeing

as they are merely sitting back and allowing neighbouring countries free and

easy access?

There’s a diffusion balance that

is going on at the moment between South Africa and Mozambique where over 400

organisations are raising and distributing funds for rhino conservation in

South Africa, yet in the area bordering on the Kruger National Park from

Mozambique there are only 3 that are trying to support conservation. With

Kruger having nearly 42% of the remaining world’s rhino population, ten percent

of that is in the top half north of the Olifants River. The remaining

percentage is south of that, with sixty of the ninety percent in the bottom quarter

of the park. Last year Kruger accounted for sixty-eight percent of the 1215 rhino deaths in the country. So have a guess where more than eighty percent of

the poachers came from…

There’s a diffusion balance that

is going on at the moment between South Africa and Mozambique where over 400

organisations are raising and distributing funds for rhino conservation in

South Africa, yet in the area bordering on the Kruger National Park from

Mozambique there are only 3 that are trying to support conservation. With

Kruger having nearly 42% of the remaining world’s rhino population, ten percent

of that is in the top half north of the Olifants River. The remaining

percentage is south of that, with sixty of the ninety percent in the bottom quarter

of the park. Last year Kruger accounted for sixty-eight percent of the 1215 rhino deaths in the country. So have a guess where more than eighty percent of

the poachers came from…

So I ask why, seven years into a war,

are there still only a few organisations that have thought to go in and try to

deal with this problem at the source, especially when South Africa’s role in

rhino poaching at the moment is merely counting carcasses and giving stats. We

need to get to the source, Mozambique, and until we address the issue there we

are going to see more and more deaths.

So why do you think nobody is doing

anything about it?

IAPF is. I’ve spent the last eighteen

months there working on joint strategy plans with the Greater Lebombo

Conservancy, a section of privately owned reserves bordering on the southern

part of Kruger National Park, which is the most critical piece of land on the planet

for rhino conservation. Sabie Game Park alone is the buffer between a quarter of

the world’s remaining rhino population and is also the world’s largest source of rhino

poaching syndicates.

It is a social issue more than

anything else. We need to be working with the communities, and I’m the guy

trying to buy time. What I’m doing is not the ultimate solution, but someone

has to do something while we figure this thing out.

Do you have anything further to say?

We need to start thinking outside of the box, and by that I mean to start thinking beyond our borders. South Africa and the rest of the world have the resources to deal with this problem, but at the moment there are millions of people trying to do millions of things. If we can all get co-ordinated, there are lots of opportunities to get involved with conservation both locally and internationally. I urge people to start understanding where this problem is coming from, and then making a stand by addressing the source.

*******

For more information on IAPF and similar organisations, please click on the Reading Rhino to your right, which I have named Elena, after the illustrator that designed it.

FOLLOW

Comments

Post a Comment